Nov 26, 2025

Nov 19, 2025

The Great Lakes Storm of 1913 is widely considered the deadliest and most destructive natural disaster in the recorded history of the Great Lakes. Often referred to as the White Hurricane, it was, in many ways, a meteorological bomb. More than 250 people were killed, 12 freighter ships sunk, and another 20 ships were stranded. The gale winds and blinding blizzard conditions were monumental and unprecedented.

The brunt of the storm lasted four long and devastating days and nights from November 7th to November 10th, 1913. Like most storm systems, it started over the Midwest United States and hit the Great Lakes with a fury when two major storm fronts of low pressure merged and were fed by the relatively warmer waters of the Great Lakes. This caused the entire storm to linger and batter four of the Great Lakes and their surrounding landmasses. Lake Huron was the worst hit. Not counting 'normal' storms, there have been over 20 such early November killer storms on the Great Lakes since records began in mid-1800s. This was the worst of them all, by far.

Hurricane-like wind gusts as high as 90 mph (145 km/hr) caused waves as high as 35 feet (11 m). Whiteout blizzard conditions developed over the entire area from Duluth/Port Arthur and Chicago in the west, Port Huron and Sarnia in the middle, to Cleveland and Buffalo in the east. Port Huron and Sarnia, along with Cleveland, were some of the worst hit cities. Cleveland broke a long-standing record of 22" (56 cm) of snow in three days and experienced wind gusts up to 80 mph (129 km/hr), all of which collapsed hydro and telephone poles and left the city isolated and paralyzed.

Massive lake freighters were tossed around like toys. Most of the ships that were lost were the big ones over 400-feet (122 m), as maybe they figured they were impregnable to any storm. They figured wrong. But, to be fair, the United States Weather Bureau was unable to predict wind direction and did not predict the severity of the storm, so ships left safe harbour not knowing what lay ahead. On the other hand, once they were into it, some decided to tough it out as opposed to trying to find safe harbour. Others were lost trying to reach safe harbour.

Just like an early November gale decades later would claim the largest Great Lakes freighter of its time, the Edmund Fitzgerald, the largest Great Lakes freighter in 1913 was the 550-foot (168 m) bulk carrier James Carruthers, the “Pride of the Lakes,” built and launched In Collingwood, Ontario only five months earlier. It sank in Lake Huron off Harbor Beach, Michigan with all 22 crew lost. It was discovered and identified only in 2025, upside down, in 190 feet (58 m) of water. It was headed from Fort William, Ontario at the western end of Lake Superior to Port Colborne, Ontario on Lake Erie carrying a full load of wheat. It is said to have likely capsized. Several bodies of the crew, along with items of wreckage, were found along the Canadian shore of Lake Huron near Kincardine and Goderich in the days after she disappeared.

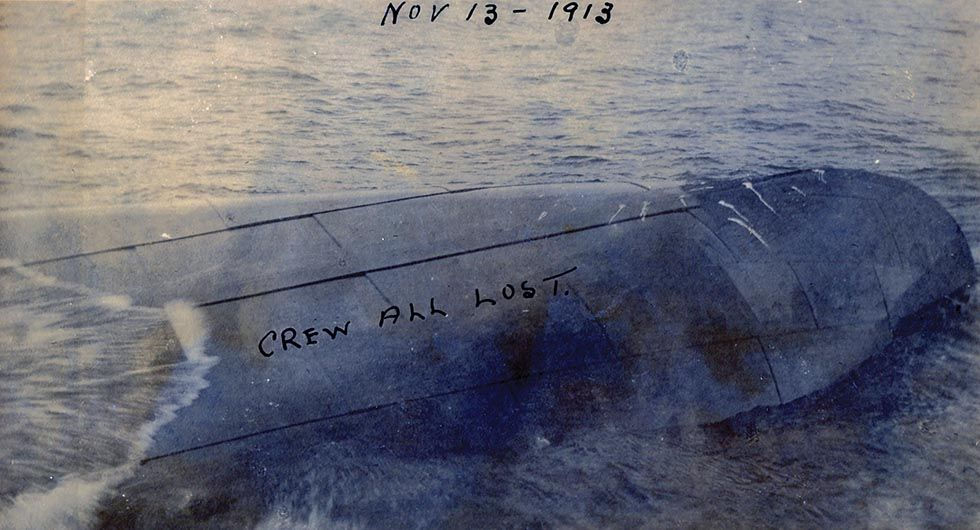

Referred to originally as the “Mystery Ship,” another freighter was found once the storm cleared, floating upside down with a short section of its bow out of the water and its stern well underwater, roughly half way between Port Huron and Lexington, Michigan, roughly 11 miles (18 km) northwest of the St Clair River at Port Huron/Sarnia. The ship eventually sank a week later and was only then identified as the three-year old, 504 foot (154 m) bulk carrier Charles S. Price. It rests upside down in 45 to 75 feet (14–23 m) of water. It was determined it also capsized. All 28 lives on board were lost.

A story of incredible survival against overwhelming odds, and a heroic rescue, played out in the extreme western end of Lake Superior where the 472-foot (144 m) bulk carrier L.C. Waldo departed Two Harbors near Duluth, Minnesota fully loaded with iron ore headed downbound for Ohio. After passing northeast of the Keweenaw Peninsula, putting the ship almost in the middle of Lake Superior, the Waldo was hammered by what survivors said was at least a 50-foot (15 m) rogue wave that pounded right over top of the ship. The wheelhouse was smashed, washing the helmsman out with it, and three walls were torn away from the deck house below the wheelhouse. Even the steel floor of the compass room was bent.

The captain tried to turn the ship around to seek shelter in the lee of the Peninsula but wave after wave smashed over the ship while blinding snow made visibility impossible. Then the ship’s steering failed and the Waldo was helpless against the 70 mph (110 km/h) winds, which drove her aground on Gull Rock near Manitou Island, just off the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula. With the bow wedged in the rocks and the hull developing cracks, the captain ordered all on board into the bow section. The two women on board, the wife and mother-in-law of a crew member, were too hysterical and had to be carried forward and uphill over the icy decks amidst the blizzard. The blizzard was so bad, fact, that the Waldo eventually became encased in ice.

All 22 crew, the two women, plus the ship’s dog, gathered forward in the unheated windlass room. No food. No dry clothes. But with a will to survive, they created a fireplace out of a bathtub and used bottomless water buckets as a chimney. They began burning whatever wood they could find or tear off the walls. They worked in shifts around the fire and exercised to keep warm.

Meanwhile, waves and winds kept pounding the Waldo as more ice formed -- encasing the survivors in hundreds of tons of ice. A passing freighter saw the peril the Waldo was in and launched a lifeboat with a single crewman who eventually reached the shore of the Peninsula. He was forced to hike several miles through the blizzard to the nearest town. He got a message to the Eagle Harbor Life Saving Station.

Eagle Harbor’s 36-foot (11 m) lifeboat was out of service, so the life saving crew had to take the 26-foot (8 m) open rescue boat the 32 miles (51 km) headlong into the storm to try to reach the Waldo. After eight miles, the boat had to turn around as the crew was literally caked in ice -- their clothes frozen solid to the boat’s seats. They hurried to fix the larger lifeboat and headed back out into the storm.

At the same time, the next lifesaving station along the coast, the Portage, recruited a tug boat to tow its lifeboat a longer but safer 80-mile (129 km) route up the lee shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula to reach the Waldo. Eventually the crews from the two life saving stations reached the Waldo within hours of each other – close to four days after the grounding. The rescue crews and their boats were encased in ice upon their arrival - forcing them to chip their way into the Waldo while the Waldo crew chipped their way out of the windlass room to reach the rope ladders for evacuation.

All 22 crew, plus the two women and the dog, were put onto the two lifesaving boats until they reached the tug, which towed them both back to their stations. Their story was truly a miracle. Both lifesaving crews were awarded medals of honor for their bravery. Almost a year later, the Waldo was hauled off the rocks, repaired and returned to service as a Great Lakes freighter and renamed the Riverton.

A shorter story is that of the 250-foot (76 m) bulk carrier Leafield of the Algoma Central Steamship Line, which sank a year earlier in August, 1912 on a shoal off Beausoleil Island in Georgian Bay with a load of ore destined for Midland, ON. After repairs to the massive tear in its hull, it was back in service, and during the storm of November 1913 was carrying a load of steel rails out of Port Arthur headed downbound for Midland once again. It made it the roughly 14-miles (23 km) from Port Arthur to the mouth of Thunder Bay, at the entrance to Lake Superior, when it is suspected to have foundered on the Angus Rocks and sank in deep water in Lake Superior. No trace has ever been found. All 18 crew were lost.

When launched in 1909, the Isaac M. Scott was said to be one of the best looking of all the large freighters on the Great Lakes. On her maiden voyage in July that year, the 524-foot (160 m) bulk carrier was running near full speed in heavy fog off Whitefish Point in Lake Superior when it rammed the downbound 420-foot (128 m) John B. Cowle. Nearly split in two, the Cowle sank quickly. Of the 24 crew onboard, 14 were lost. The captains and pilots of both vessels were held accountable for excess speed and not proceeding according to weather conditions.

Four years later, the Scott was carrying coal from Lake Erie upbound headed for Duluth at the far west end of Lake Superior. It was last seen entering Lake Huron from the St. Clair River in the afternoon of November 9th. As it headed north up the lake, it battled heavy northwest winds. At that same moment, the worst of the gale quickly shifted from northwest to northeast, meaning the wind and waves were attacking from different directions. The Scott and its crew were battling for survival.

For whatever reason, the Scott decided not to turn into Saginaw Bay, where it might have weathered the storm, but instead turned to head up into open water toward Sault Ste. Marie. She was not found until 1976. upside down in around 200 feet (61 m) of water, some six miles (10 km) north of Thunder Bay Island, MI. All 28 crew were lost. It had obviously capsized. The Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Underwater Preserve was created to preserve the 116 historically significant shipwrecks in the area, including the Isaac M. Scott.

The oldest ship believed to have been lost in the Great Lakes Storm of 1913 is the 250-foot (76 m) bulk carrier Wexford built in 1883 in England. She was headed from Lake Superior to Goderich, Ontario in Lake Huron with a full load of grain. The ship had spent the previous night biding its time docked at Sault Ste. Marie before heading out through the Soo Locks and into the St. Mary’s River in the morning of November 8th. It anchored that afternoon in Hay Bay, about 45 miles (72 km) east of The Soo, before heading into the main body of Lake Huron on November 9th.

The weather soon struck with the driving snow and falling temperatures of the “White Hurricane.” The ship disappeared. It was not discovered for 87 years until she appeared in 2000, mostly intact and sitting upright in 80 feet (24 m) of water some 7 miles (11 km) northwest of Grand Bend, Ontario. That means the Wexford rests 20 miles (32 km) further beyond its intended destination of Goderich. The oldest ship was said to have had the youngest crew. All 18 of them were lost plus two guests.

As Gordon Lightfoot said in the last two lines of his famous ballad, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, “Superior, they said, never gives up her dead / When the gales of November come early.” On November 10th, 1975, some 62 years to the day after the devastating Great Lakes Storm of 1913, another violent storm claimed the largest Great Lakes freighter of its time, the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Following the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald, the first network of eight data buoys in the Great Lakes was deployed in 1979 by the US and Canadian governments. Buoy technology improved with enhanced data capture capability throughout the 1980s and 90s, giving freighters more intel to avoid another deadly gale. Today, dozens of real-time smart buoys measure a range of conditions including wind speed and direction, air and water temperature, barometric pressure, wave height, and water quality parameters like dissolved oxygen and chlorophyll. Live tracking of Great Lakes commercial ship locations is also provided.

If only this had been available in the early days of November 1913. But, through the tragedy, the storm served as a wake-up call. It resulted in much needed improvements in weather forecasting and in communications on the Great Lakes and in ship loading and the securing of loads. We should hope to never see a gale like we did with the White Hurricane ever again. #culture

Fascinating story. Thank you for this feature. A great read.